Make a career of humanity. Commit yourself to the noble struggle for equal rights. You will make a better person of yourself, a greater nation of your country, and a finer world to live in.

Guest Blog by Bob Williams, CommunicationFIRST Senior Strategic Advisor

I am excited to be working with CommunicationFIRST, the only organization in the United States led by and for individuals with disabilities and conditions who need and use augmentative and alternative communication (AAC) strategies to express ourselves. Collectively, we can and must advocate together for the human and civil right to effective communication for all children and adults, regardless of condition, disability, and support need. Here is why I believe this is CommunicationFIRST’s urgent, essential duty.

As my bio illustrates, by all objective standards I have had and continue to lead a full and successful personal life and career. My journey has not always been a sure one, however.

Born in 1957, I grew up at a time when the chances were slim to none for a kid like me with significant cerebral palsy and little to no understandable speech to even enter a public school—let alone to be assured of receiving a good education, graduating from high school and college, having a career, getting married, or having a family.

At times, my parents, brothers and sisters, and I endured discrimination because of my mere presence in society. Once, we were told to leave a restaurant simply because I drooled. When our hometown barred me from going to school, my parents moved our family across the state just so I could be educated.

Ever since I can remember, I have been extremely proud of all the love and hard work that my family, teachers, friends, allies, mentors, and I have invested in helping to shape and set the life trajectory that I am on.

With this pride, though, comes a deep recognition of the injustices that millions of children, youth, working age adults, and older persons continue to face because they must rely on one or more forms of AAC to express themselves and be understood. I have known many who have experienced and continue to face such barriers.

One of these people was Viola Washington, the greatest teacher I have ever had. Vi and I got to know each other in the 1980s when I worked on a team of court-appointed monitors overseeing conditions during the closing of Forest Haven, an institution run by the District of Columbia. I am not certain why, but Vi was committed there near the end of World War II when she was 7 years old. When we met, she was in a wheelchair for a few hours each day, but had spent most of the past 40 years in bed like many others. Some of the staff who worked with her shared our belief that she needed an AAC system. Others who worked on her ward, however, questioned her ability to use and understand language. Until, that is, one day when she was present in a meeting with her treatment team. Her physician mistakenly referred to her using another resident’s name. Vi broke into unabashed laughter and all the rest of us there—except the doctor—got the joke as well. Her laughter transformed hearts and minds as well as expectations about Viola and our own selves. On that day, we received a lesson in liberation.

While molded by many factors, I believe my life trajectory has been made possible by the following above all else: The love and belief that my family and others have had in me. From a very young age, I developed and was provided a ready supply of ways to communicate and connect. My mom said she knew I could keep a beat and had things to say when I pretended to lead a band or played 20 questions as a toddler. At 6 or 7, I learned to type on an IBM electric typewriter, which convinced my doubtful teacher that I could both read and write.

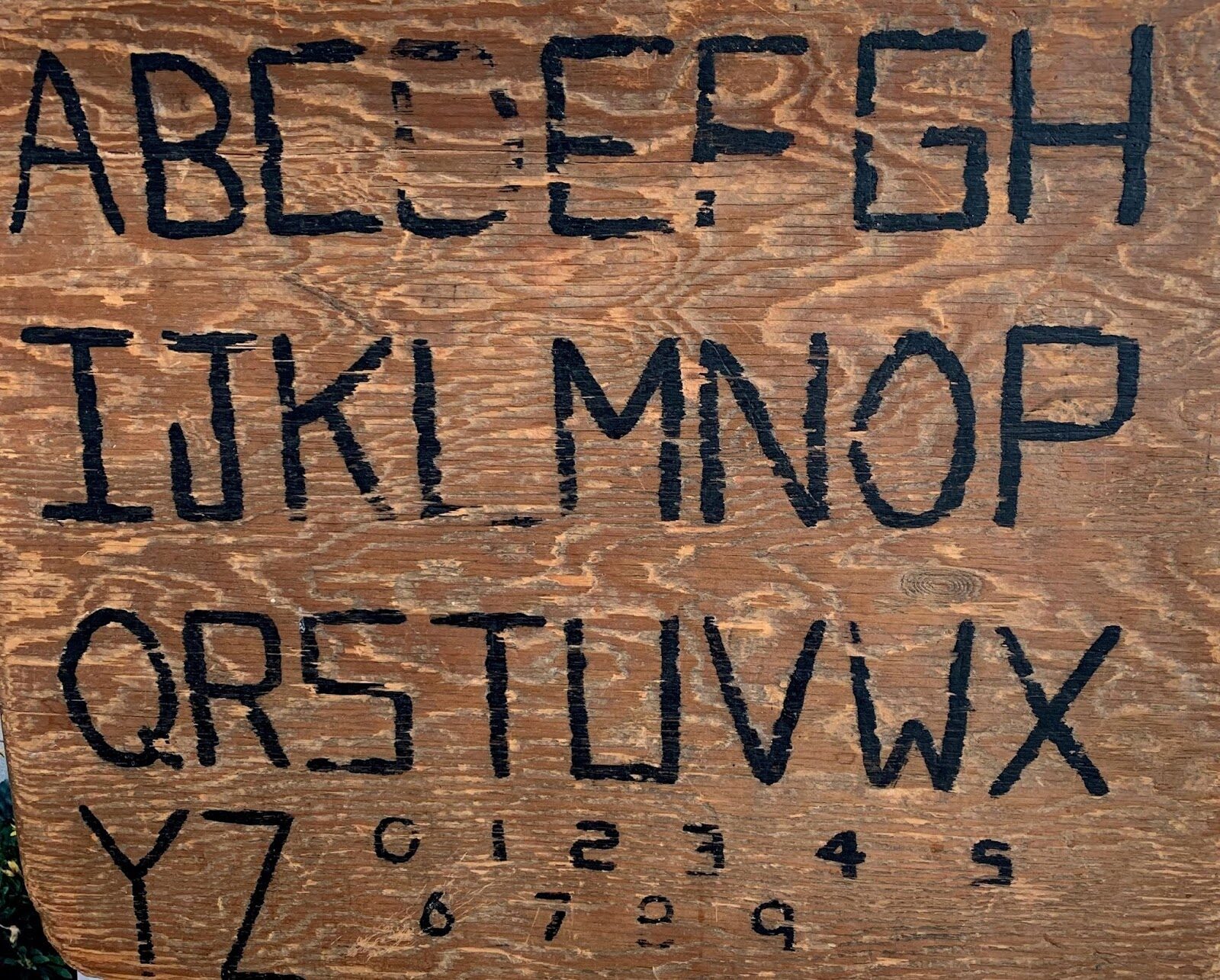

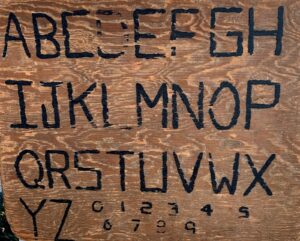

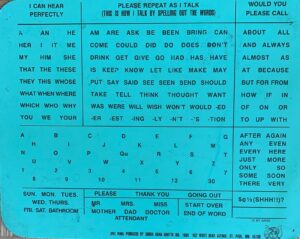

When I was 13, a camp counselor painted the alphabet in bold black capital letters on a piece of wood (image above). I pointed to letters to spell out words and sentences. A year or two later the same counselor handed me a green board with letters, numbers, words, and phrases—the Hall Roe communication board, named for the man with cerebral palsy who helped designed it (image right). This board saw me through high school, college, dating, internships, and my first two full time jobs. In fact, I used that board to lobby with others for the passage of the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA).

A week after the ADA became law, I participated in the Augmentative Communication Empowerment and Supports Institute—ACES—at Temple University in Philadelphia. With about a dozen other people who used AAC, I learned in the summer of 1990, as a 33-year-old professional, to use my first speech-generating device. I have used successive iterations of this same device ever since. Being able to use such technology, combined with and multiplied by all that the Internet and digital innovation offers, has transformed my and others’ lives and futures in ways and degrees that remain unfathomable to many.

The access to AAC and multiple means of expression that I have enjoyed throughout my life are unfortunately not the norm for far too many people, regardless of their age, race, ethnicity, gender and sexual identity or expression, and disability or other condition.

The paramount reason CommunicationFIRST exists is to confront this reality and to work to eliminate the prejudice, stereotypic thinking, discrimination and other barriers that perpetuate it. The most powerful way we, as people who need and use AAC, can do this is by sharing our stories with each other and the public. By doing so, we begin to better understand what we share in common, what unites us, and what we must seize on to guide our advocacy.

I recently met Jordyn Zimmerman when she was finishing up a summer internship in Washington, DC, and would soon return to complete her undergraduate studies in education policy from Ohio University. Judy Heumann—a close friend, disability rights leader, and CommunicationFIRST Board member—suggested we meet because we share the same vision and commitment. As I strive to do, Jordyn also envisions making what Dr. King called “a career of humanity” by working for equal rights and equal justice. We talked about what it was like to work in Washington, DC, and in public advocacy.

Jordyn and I talked also of something just as fundamental that we share. Jordyn, who is autistic, types on an iPad with a synthesizer to express herself. Unlike me, though, she told me she had little to no access to language or means to communicate until she was a teenager. No one should have to wait that long to exercise such a basic human need and human right. Imagine how anyone could make the quantum leap she has made to living life as a Millennial in the 21st century without finding a way to communicate and connect.

Jordyn and I have agreed to stay in touch, to listen and learn from each story we hear, and to work to make CommunicationFIRST for a reality for all. These are the essential steps we all can and must take to heed Dr. King’s call.