by Alyssa Hillary Zisk, Guest Contributor

“Why are you using a male voice?” I’m sitting in the car next to a professor who is giving me a ride back to campus.

I’m not sure what to type. The first question is, why am I using any voice? I normally prefer to have people read what I type or write. That question has an easy answer: I’m talking to someone who is driving. He can’t exactly turn to read my screen safely. So, if I want to be able to communicate with him in language on the ride back to campus, I need to choose a voice for speech output.

Unfortunately, the voices are all listed as being men’s, women’s, or in a couple cases, girl’s or boy’s voices. I’m non-binary. There isn’t a voice available that matches my gender. There is Q, the genderless voice, but it’s not an option for any of my AAC apps (yet?).

If I’m going to use voice output, I have to choose a voice that doesn’t match my gender.

If I have to choose a voice that doesn’t match my gender, I’d rather not be the only one who knows I’m doing that. Just like if I’m going to be in a room where everyone except me is the same gender, I’d rather not be the only one who knows.

I’m not a man, but I do use a male voice because I’m trans.

But a discussion on gender identity, gender presentation, and the ways they interact with assistive technology is a bit much for me to type on an onscreen keyboard balanced on my knees, when we’re within a quarter-mile of our destination. I shrug.

“Can you change it?”

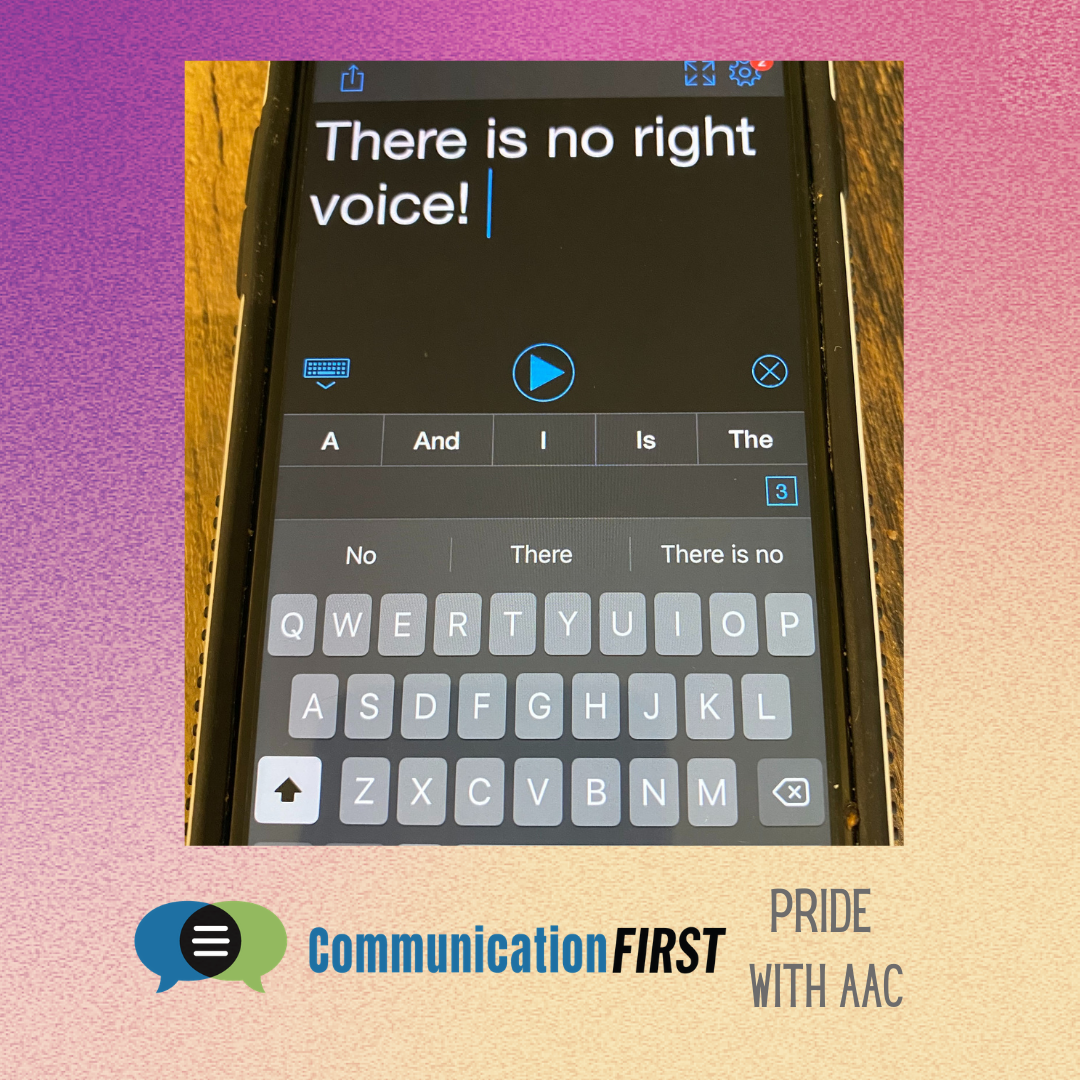

I say “I don’t want to,” but that’s only half-true. I’d like to find a gender-neutral voice I can actually use, and then change all my AAC apps to use that voice. But given the options that are currently available, no, I don’t want to change the voice on my iPad.

Except, of course, when I can turn it off entirely. That’s not always possible – not everyone is literate, and not all situations allow for reading. But when I can get away without using voice output, that’s mostly what I do. I’ll sit across the table from the person I’m talking to and type in Flip Writer without hitting the button for speech output. Or I’ll open a word processor document on my computer, increase the font size, and project my screen to the room.

If I want to take notes privately, I’ll need a separate device to take notes on, a way to block part of the projection so the rest of the room doesn’t see my whole laptop screen, or to have a separate window for my notes with the font size set too small for the rest of the room to read, even projected. (Not that I know how good their eyesight is … and there are limits to how small I can make the text and still be able to read it myself.)

Because I can’t use a right AAC voice that matches my gender, trying not to use a wrong voice is harder, and not always possible. When I have to use voice output, “least bad” is the best I can do. And I have direct control over all my devices. I can put in that work, to minimize the wrongness. People may ask hard questions they think are easy (“why are you using a male voice?”), but I am in the privileged position where no one else can change the voice “for me” so they could “help” (misgender) me. I’m in a position to say no, I don’t want to change the voice to one that matches the gender people (incorrectly) assume for me. But many AAC users are denied this autonomy by people who think they know what’s best.

This pride month and beyond, keep in mind that AAC users may prefer voices that don’t match the gender you think we have. Sometimes it will be because we’re trans. Sometimes it won’t. Regardless, if it’s going to be how we communicate, your job is to let us use the voice (or lack thereof) that works for us.

Alyssa Hillary Zisk is a member of CommunicationFIRST’s Advisory Council. They recently completed their Ph.D. in interdisciplinary neuroscience from the University of Rhode Island, where their dissertation focused on a particular kind of brain-computer interface, which people with ALS can sometimes use for AAC. They also do work related to AAC and autistic adults. Alyssa blogs at http://yesthattoo.blogspot.com/, Tweets at https://twitter.com/yes_thattoo, and their academic work can be found at https://uri.academia.edu/AlyssaHillary.