CommunicationFIRST’s Style Guide

About the Guide Below

About the Guide Below

We are often asked about the words we use to refer to ourselves and the people we aim to serve: people who cannot rely on speech alone to be heard and understood. We appreciate the question and the chance to respond. What follows is CommunicationFIRST’s own style guide, not a directive for others to follow.

As we build the first civil rights organization led by and focused on the estimated 5 million people in the United States with speech-related communication disabilities, we are exceptionally conscious of the power and importance of language. This is particularly true when describing what we do, who we are or seek to represent, and what we aim to achieve.

We are finding our own voice, telling our own truths, and expressing our own individual and collective stories. We are naming ourselves. And we choose our words with great care. This document explains our reasoning behind the words we currently choose to use and avoid. It is the consensus result of many hours (over several years!) of thoughtful reflection, discussion, and debate among the diverse members of CommunicationFIRST’s Board of Directors, Advisory Council, and staff. It is a work in progress.

-

-

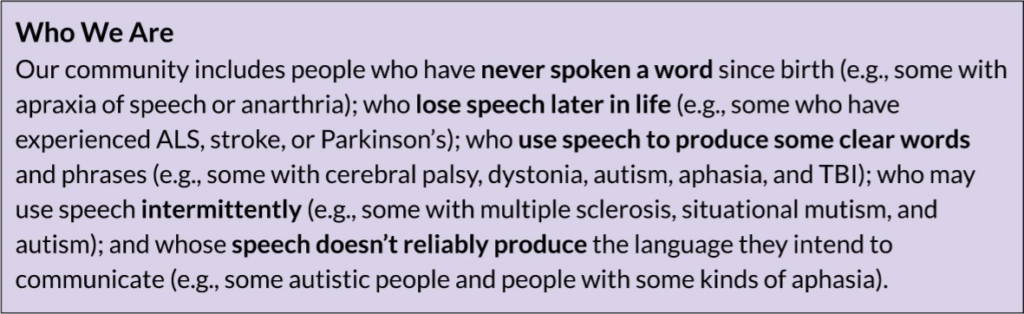

- Our Community Is Diverse. We know that people who use or need any kind of expressive communication tool, support, or strategy due to a speech-related disability or condition have much in common, but we also have many different disability experiences, medical conditions, and communication strategies. Because of biases and assumptions, we all face misunderstanding, low expectations, and discrimination. The justice we seek also is the same. But our varied life experiences also create unique identities. People who lose speech due to an acquired condition, like ALS or Parkinson’s, have different journeys than people who are born with a lifelong condition, like autism or cerebral palsy. Because we choose different ways to describe ourselves, we may disagree about whether a term is liberating or offensive. These discussions can be difficult, but they are also natural, healthy, and necessary. Language can divide us, or we can use it to unite our common humanity. We aim to use words that honor the diversity of our community, while keeping in mind that too many of us still lack access to the tools and supports necessary to share our language preferences.

- Respecting Individual Choice. CommunicationFIRST respects the right of each person to describe themselves however they choose, even if that preference differs from how we might describe a broader group. When in doubt, ask.

- Language Evolves. What follows reflects the words CommunicationFIRST understands and chooses to use or avoid right now, as of the date of publication. We know that community understanding and preferences will change, and that we will adjust the words we use over time.

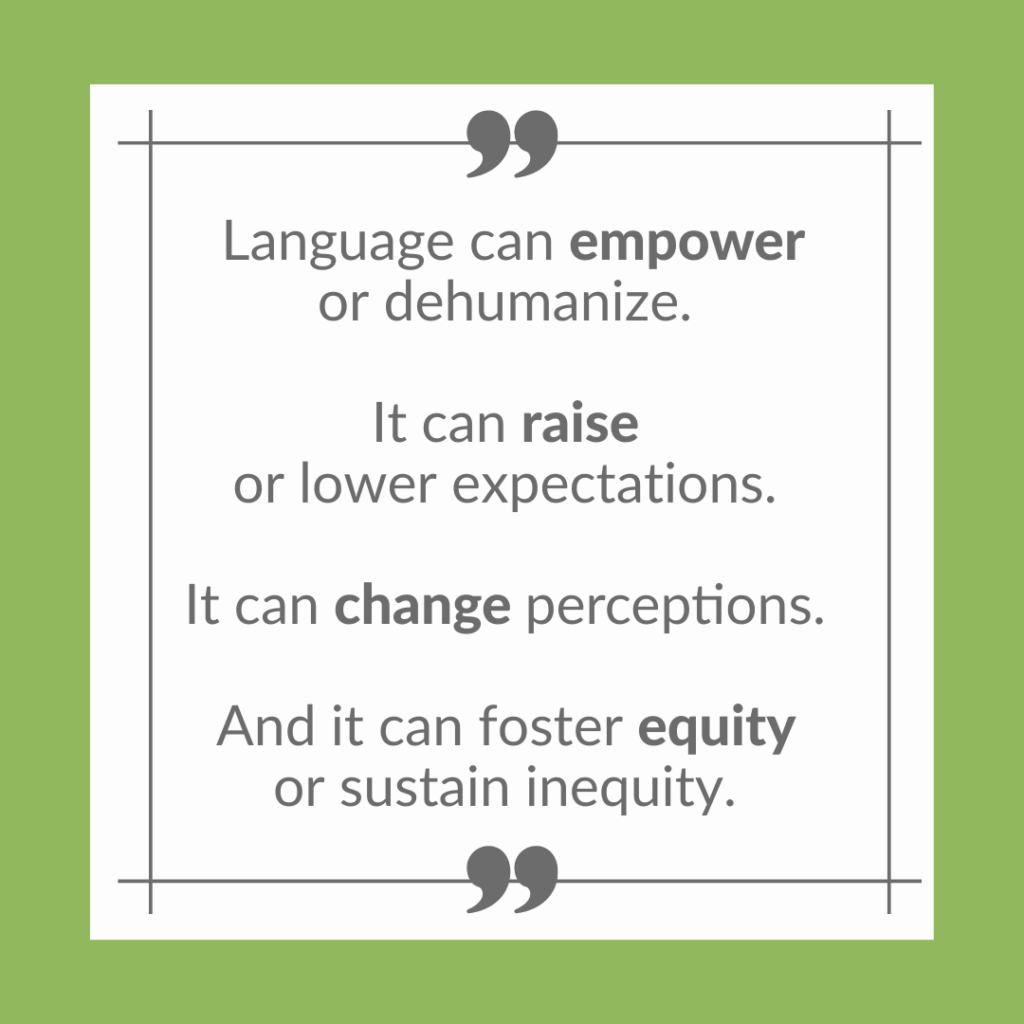

- Language Is Powerful. The words we use have consequences. We must avoid further marginalizing those who have been denied access to free expression. This is not an effort to be politically correct, to police other people’s language, or to suppress opinion. Language can empower or dehumanize. It can raise or lower expectations. It can change perceptions. And it can foster equity or sustain inequity. Words alone will not secure justice or equality of opportunity. Yet, how we describe who we are, our hopes, our fears, and the future we want to create is vital. And the words we use must be our own.

- Asserting the Right To Name Ourselves. The power of free expression is vital to exercising all civil rights and liberties. Free expression includes access to language, naming who we are, shaping our lives, and conveying how we expect others to recognize, respect, and relate to us as their equals. People denied access to robust, language-based augmentative and alternative communication (AAC)* are robbed of this power. We disproportionately endure lifelong illiteracy, institutionalization, exclusion, poor health, and worse. We are regarded as having little to no ability, reason, and therefore no need or right to effectively communicate, or to lead lives of our own direction. The words most frequently used to describe us continue to be what others choose. Self-identifying is critical to every liberation movement.

* AAC includes all forms of communication other than speech, including gestures, eye gaze, vocalizations, taking someone by the hand, facial expressions, and body positioning. Language-based AAC is any type of AAC that allows the person to communicate using words.

- Language Impacts Culture and Mindset. It is hard to imagine now that, well into the last century, deaf people were described as “deaf and dumb,” an odious term coined by Aristotle, who felt “that deaf people were incapable of being taught, of learning, and of reasoned thinking.” CommunicationFIRST works to counter the dangerous assumption that not being able to rely on one’s own speech to be heard and understood means we cannot understand and express language. This will require a huge shift in culture and mindset, but this shift is possible. Such shifts continue to occur in the United States with respect to how people of color are perceived and treated. We are also encouraged by the cultural acceptance the LGBTQIA+ community has achieved over the last 25 years, including the creation of new language. We recognize that these civil rights movements overlap with us, potentially compounding both harm and liberatory lessons.

- Share Your Feedback! We invite others who use expressive communication tools and strategies, including various forms of AAC, to fill out the short survey at the end to let us know what you think.

- Our Community Is Diverse. We know that people who use or need any kind of expressive communication tool, support, or strategy due to a speech-related disability or condition have much in common, but we also have many different disability experiences, medical conditions, and communication strategies. Because of biases and assumptions, we all face misunderstanding, low expectations, and discrimination. The justice we seek also is the same. But our varied life experiences also create unique identities. People who lose speech due to an acquired condition, like ALS or Parkinson’s, have different journeys than people who are born with a lifelong condition, like autism or cerebral palsy. Because we choose different ways to describe ourselves, we may disagree about whether a term is liberating or offensive. These discussions can be difficult, but they are also natural, healthy, and necessary. Language can divide us, or we can use it to unite our common humanity. We aim to use words that honor the diversity of our community, while keeping in mind that too many of us still lack access to the tools and supports necessary to share our language preferences.

-

The Words We Currently Use

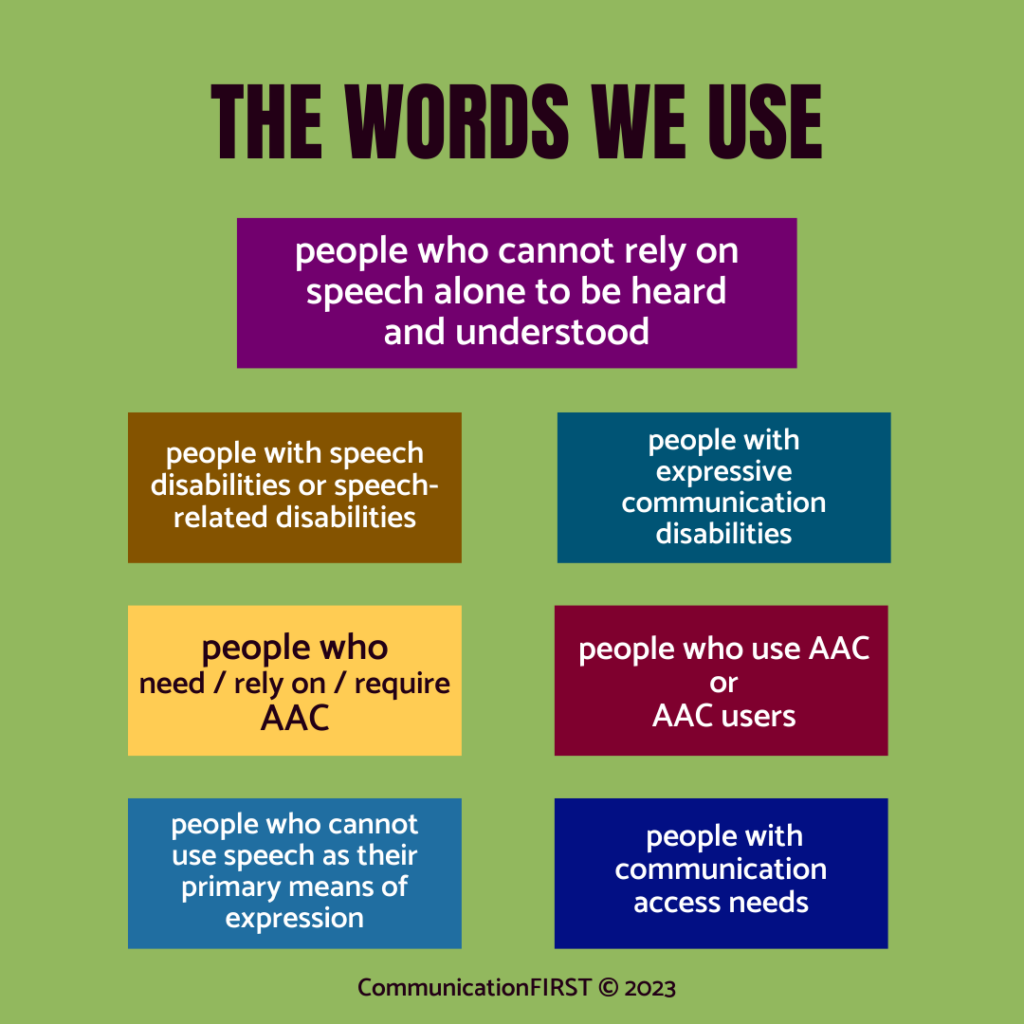

There is no one, universally accepted term that describes our diverse community. As such, CommunicationFIRST chooses to be descriptive. We currently use phrases like “people who cannot rely on speech alone to be heard and understood” to refer to everyone whose rights and interests we work to advance.

In addition to being inclusive, the phrase “people who cannot rely on speech alone to be heard and understood”:

- Is easily grasped by the general public, policy makers, and media (including people who don’t know the term “AAC”).

- Assumes that we have something to express, focuses on our need and right to be understood, and emphasizes that there are other ways besides speech that we can be heard.

- Asserts that we do have the ability to hear, understand, and respond to others. We value what people have to say and respect others by responding. We expect the same in return.

- Highlights the fact that communication always involves at least two parties, and tries to shift the focus, “blame,” or burden of addressing any communication barrier away from the speech-disabled person to the context and interaction.

- Respects people who, due to personal, cultural, generational, or other factors, may not identify with “disability” terminology.

- Includes people who cannot speak at all, as well as people who may be able to use speech some of the time (e.g., in certain contexts, at certain times of the day, or with specific people) to communicate their thoughts effectively and be understood by others.

Depending on the context and audience, we may also use the following terms to broadly describe our community:

- people with speech or speech-related disabilities

- people with communication access needs

- people with expressive communication disabilities

- people who cannot use speech as their primary means of expression

- people who need / rely on / require AAC

- people who use AAC

- AAC users

The Words We Currently Avoid

Nonverbal

The root of this word, “verb,” comes from the Latin verbum, meaning “a word” or “language.” To describe someone as nonverbal, then, is to say that they cannot understand or use language.

But this is a factually inaccurate way to describe someone who cannot speak. Speech is the motor process of expressing language. Language is a cognitive process that involves perceiving, understanding, and producing ideas and concepts through the symbolic represent ation of words. Just because someone cannot rely on speech does not mean that they do not understand or cannot use language. Speech is just one way to express language. It is impossible to know what a person who cannot speak actually understands unless they have been given access to appropriate communication tools (and the training and supports to be able to use them).

ation of words. Just because someone cannot rely on speech does not mean that they do not understand or cannot use language. Speech is just one way to express language. It is impossible to know what a person who cannot speak actually understands unless they have been given access to appropriate communication tools (and the training and supports to be able to use them).

There is no anatomical basis to assume that someone with a speech disability is incapable of understanding language.

Yet, as any AAC user who cannot rely on speech to be heard will tell you, it’s widely and wrongly believed that an inability to speak is an inability to understand. Other people regularly talk about us like we cannot understand you and like we are not even there. The assumption that we lack language dehumanizes us, and makes us invisible.

The term also suggests that it is a status that cannot be changed, which can contribute to a vicious cycle. When we don’t have the tools we need to communicate, people will assume we can’t communicate. When people assume we can’t communicate, they won’t give us the tools we need to communicate.

Note that many prefer the term “nonspeaking” over “nonverbal,” especially in the autistic community. CommunicationFIRST may use the term “nonspeaking” when referring specifically to the autistic community, and, of course, with any individual who prefers that term. However, there are people in our community who can use spoken words and forms of AAC that generate speech or type for others to read and self-identify as “speaking.” For this reason, we do not use the term to refer to our population more broadly.

Severe or Profound

There is nothing positive about these words. They have no scientific or clinical validity as a measurement. Instead of providing any useful or precise information about our needs, these words can work to cause fear and pity. It’s hard to imagine that someone described as “severe” or “profound” could be a friend, ally, classmate, leader, or neighbor in your community.

We aren’t extreme, foreign, rare, or inhuman. We are simply people who may need certain accommodations, supports, or services to live well. Describing those supports and services, instead of using dehumanizing words like “severe” and “profound,” focuses on making sure that we get what we need. These words are also often associated with terms such as “mental retardation.” This old language must be retired.

► Instead of calling someone or their condition “severe” or “profound,” be descriptive. You can be as nonspecific as saying they have “disability-related access needs,” or you can describe a specific unmet need (e.g., “They cannot use speech to be understood, but we haven’t yet found a form of AAC that works for them.”) (Note that the alternative term “significant” can also be seen as negative and have negative consequences. As a result, CommunicationFIRST will not use the term “significant” to describe our population generally, but may use it in specific policy or advocacy settings, especially because the term “significant disability” is used in some laws and regulations, including the Rehabilitation Act.)

Disorders, impairments, and deficits

Disability is universal, and a natural part of human diversity. Communication comes in many forms other than speech, and each form is valuable and worthy of respect. Plus, communication isn’t something we have—it’s something we do together. Communication is a collaboration—a two-way street—where we work together to exchange, express, receive, and understand information. When we view communication like this, telling one member of the conversation that they have a “deficit” doesn’t make much sense. Why isn’t it the receiving part of the conversation that has the deficit?

Disability is universal, and a natural part of human diversity. Communication comes in many forms other than speech, and each form is valuable and worthy of respect. Plus, communication isn’t something we have—it’s something we do together. Communication is a collaboration—a two-way street—where we work together to exchange, express, receive, and understand information. When we view communication like this, telling one member of the conversation that they have a “deficit” doesn’t make much sense. Why isn’t it the receiving part of the conversation that has the deficit?

These terms are rooted in the “medical model” of disability, whereas the disability community prefers a “social model” of disability.

► Instead of “disorder,” “impairment,” or “deficit,” consider the more neutral terms “condition” or “disability,” though note that different people may prefer one of these terms over the other (e.g., people who acquired their speech loss later in life may identify less with the disability community and terminology). If you’re not sure which word to use, be descriptive: “They use AAC” or “They require AAC to be understood,” instead of “they have a speech deficit.” Whenever possible, ask people how they describe themselves.

Complex communication needs

We believe this term, which emerged from a US government-organized consensus group on AAC in 1992, is similar to the harmful, othering, and inaccurate outdated euphemism “special needs.” People with disabilities don’t have “special” or “complex” needs. We have the same needs as everyone else to communicate and be understood. We may employ complex strategies and require tools, supports, and services that may involve sophisticated technology, training, dedication, and ongoing support, but there’s nothing complex about our need to communicate and be understood. Nor is it that complicated or difficult to get to know us or include us.

► When describing our needs, be clear and descriptive. Don’t use a euphemism, or a word that is used to avoid saying something that someone thinks is unpleasant or offensive. The same goes for describing our communication. Explain that we use AAC, or be specific about the kind of AAC we use, or describe how we communicate.

Non-communicative

It’s nearly impossible for anyone to be totally “non-communicative.” AAC includes all forms of communication other than speech, including gestures, eye gaze, vocalizations, taking someone by the hand, facial expressions, and body positioning. All of those things are communication! If a communication barrier exists, the onus is—or should be!—on the people around the person without a communication disability to remove that barrier or build the bridge. Labeling us “non-communicative” also suggests a status that cannot be changed. And it removes the sense of urgency to find and provide us with language-based communication tools and supports.

► Instead of calling someone “non-communicative,” describe and respect the ways they already communicate: “She doesn’t yet have an effective, language-based form of AAC to express herself, but she’s extremely effective at communicating her daily needs and preferences in other ways.”

Similarly, describing someone as a “beginning,” “emerging,” or “emergent” communicator disregards all the forms of communication the person has already figured out to express themselves on their own, with no support. And it privileges certain types of communication above others.

► When trying to convey the idea that the person is learning a certain type of AAC, say so: “The student is being supported to learn how to use [form of AAC] to communicate.”

It is impossible to know that someone has “no language.” Over and over it has been demonstrated that people with no language-based expressive communication may have full receptive understanding of words. The inability to demonstrate language by using speech or sign or gesture is not evidence of its absence.

Behaviors

When people move or make noises in ways that are unexpected, unfamiliar, or unwanted, they are often labeled as “having behaviors.” Human beings move in different ways. Some movement is planned and intentional. Some is unplanned and unintentional. Some is both at once. Some is triggered by sensory reactions to environmental inputs or lack of input, pain, trauma, emotions, or habit. No human is merely a bundle of behaviors. When we characterize human movement this way, we are more likely to view both the movement—and the human doing that movement—as “other” or inhuman. “Behaviors” become something to control or fix; “behaviors” often become a prerequisite to “address” before someone is given access to AAC. The word “behaviors” erases and dehumanizes the human behind the movement.

► In avoiding the term “behaviors,” we try to be specific and descriptive about the what the person is doing. Or we say something like, “She’s acting in ways that communicate her needs because she has no other way to communicate.”

Clients, consumers, or patients

These terms are often used by service providers to describe us, and they may make sense in certain contexts. CommunicationFIRST, a disability-led organization, however, does not use these terms to refer to our population generally because they can be “othering” and dehumanizing. In addition, the “services” employed, taught, or “provided” to assist others to understand what we want to say are actually for the benefit of, and are a service to, everyone involved—us and our interlocutors.

Communicative competence

This term was coined in 1989 to help communication professionals better understand and analyze all important interpersonal aspects of communication that everyone needs. The goal was to challenge beliefs that being given the tools to communicate a basic request was “good enough” for anyone. In 2014, the authors revisited and expanded the framework after 25 years of technological and other developments in the field.

The ideas behind the “communicative competence” framework are helpful. In practice, however, the term itself may inadvertently shift the burden of addressing a communication barrier to the person who has the fewest tools to address it. The term also suggests a binary—that one is either a “competent communicator” or an “incompetent communicator.” When someone is seen as “communicatively incompetent,” they’re more likely to be denied access to robust, language-based AAC, segregated, or even institutionalized than they are to be given the supports and services they need to develop new skills. We urge that a new, less harmful term be adopted to describe the framework.

Survey

If you have a speech-related disability, please let us know what you think and what terms you prefer by filling out this short survey. We value your opinion—thank you for helping us improve this resource with your input! The survey will remain open indefinitely.

Additional Resources

(Note: Inclusion of a resource below should not imply endorsement)

- The Facebook group “Ask Me, I’m an AAC User!” regularly takes questions and discusses preferred and non-preferred terminology, including why certain terms can be harmful.

- Erin E. Andrews, Robyn M. Powell, & Kara Ayers (2022), “The evolution of disability language: Choosing terms to describe disability,” Disability and Health Journal, 15(3)

- Kathy Bates (2023), “She’s Nobody Special”

- Kristen Bottema-Beutel, Steven K. Kapp, Jessica Nina Lester, Noah J. Sasson, & Brittany N. Hand (2021), “Avoiding Ableist Language: Suggestions for Autism Researchers,” Autism in Adulthood, 3(1)

- Lydia X. Z. Brown, “Glossary of Ableist Phrases”

- CoorDown (2017), “Not Special Needs” (2 minute open-captioned humorous video)

- Crippled Scholar (2017), “Euphemisms for Disability are Infantilizing”

- Miliann Kang, Donovan Lessard, Laura Heston, & Sonny Nordmarken (2017), “Identity Terms,” in Introduction to Women, Gender, Sexuality Studies

- Steven Kapp (2023), “Profound Concerns about ‘Profound Autism’: Dangers of Severity Scales and Functioning Labels for Support Needs,” Education Sciences, 13(2)

- National Association of the Deaf, “Community & Culture”

- National Center on Disability and Journalism, Disability Language Style Guide

- NeuroClastic (2021), “On Using NonSpeaking, Minimally Speaking, or Unreliably Speaking over “Non-Verbal”: NonSpeakers Weigh In”

- New Jersey Autism Center of Excellence’s Language Guide

- Shruti Rajkumar (2022), “How to talk about disability sensitively and avoid ableist tropes,” National Public Radio

- Bryony Shannon (2021), “Words that make me go hmmm: Vulnerable”

- Stimpunks Foundation, “Nonspeaking”

- Thinking Person’s Guide to Autism (Sept. 4, 2023), “Grave Concerns About Profound Autism“

- University of Michigan, Language Matters, “General Language, Prejudice, & Discrimination”

- Nick Walker (2021), “Person-First Language is the Language of Autistiphobic Bigots”

- Alyssa Hillary Zisk, Lily Konyn, & David Niemeijer (2023), “What AAC terminology should I use?: Insights from a community survey”

Version 1.0 (July 2023)

CommunicationFIRST © 2023