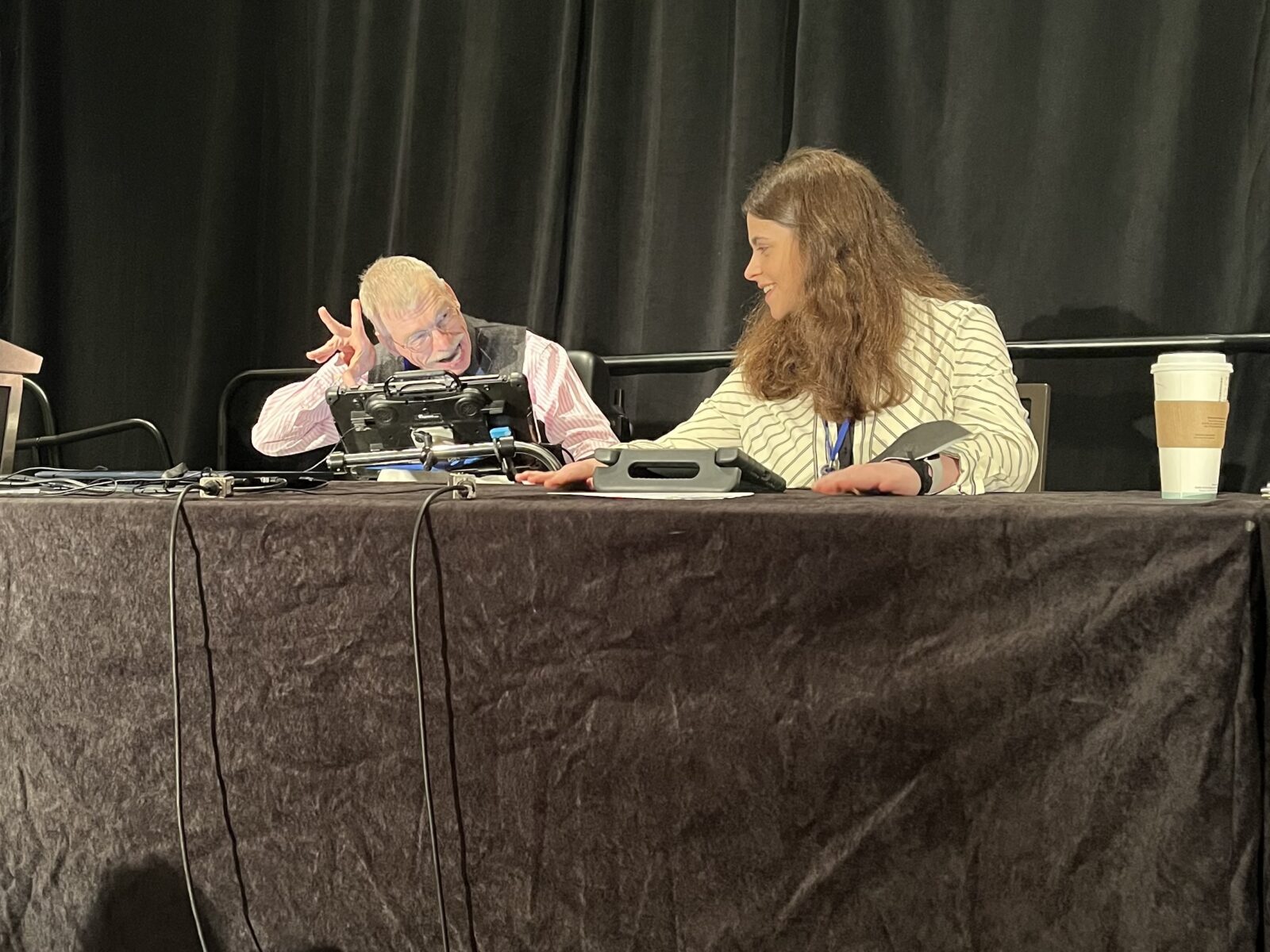

Bob Williams’s Literacy and AAC presentation was first given at the Future of AAC Research Summit on May 14, 2024, in Arlington, Virginia. Bob is the co-founder and Policy Director of CommunicationFIRST and has advanced the rights and opportunities of children, working-age persons, and older adults with disabilities for over 40 years by creating community living services, helping to pass the ADA, and administering the federally funded developmental disabilities and independent living networks.

An open-captioned film of Bob’s presentation can be accessed below.

Video production by Dana Patenaude (Penn State University/the RERC on AAC).

It has been great to spend the last day with you all, and I am looking forward to continuing the conversations we are engaged in. The subject of literacy, AAC, and the power of reading and writing are immensely important and personal to me. In addition to having used multiple means of AAC pretty much simultaneously throughout my life, I have worked to help design, implement, and improve public policy and equal opportunities for children, working age persons, and older adults with significant disabilities. My comments today reflect both sets of expertise.

To state the obvious, the US has a checkered past and present concerning literacy. An estimated 130 million adults under age 75 in our country are functionally illiterate. 54% of all adults living today in the United States read at less than a 6th grade level. 81% of 4th graders who qualify for free or reduced price school lunches are, “Less than proficient at reading.” None of this is new. Until recently, many children and adults were legally barred from becoming educated at all based on one or more of the following: their race, gender, national origins, disability, language, First Peoples-hood, religion, and other traits. To make life more equitable, future research must focus on unraveling the social milieu that perpetuate these dynamics, and public policy must be refashioned accordingly.

Let us be clear. Having or being presumed to have multiple significant disabilities grossly circumscribes the opportunity and agency of millions of people to use reading and writing to define and pursue their lives. Because of the research many of you and your colleagues continue to do, this above all, is clear. But, and this is important, disability should not continue to be misconstrued to justify consigning those needing AAC as infants and toddlers, public school students, teenagers, working age persons and older adults to having or being treated as having few literacy skills regardless of when they became disabled.

Researchers estimate that 70 to 90% of people with significant disabilities, including those who require AAC, have few, if any, functional reading and writing skills. These estimates are dated and must be updated, but we know this much for certain today: the percentage of people who lack language-based AAC and the percentage who lack basic literacy and/or are wrongly stamped as being illiterate for life are absurdly and unjustifiably high. What makes this even more of a nationwide disgrace is these injustices are still inflicting enormous harm. Fully 50 years after Section 504 and Public Law 94-142, the precursor to IDEA, and over 30 years after the ADA became law, this is still a hideous defining factor in the lives of unseen, unheard, and uncounted numbers of children and adults.

What is terribly wrong with this picture? Everything, simply everything, is wrong with it.

Learning, regaining, and maximizing the power of reading and writing should never begin or end at the schoolhouse door for any person.

We at CommunicationFIRST are passionate about improving literacy learning opportunities and outcomes for all of our country’s estimated 5 million people who need AAC. Especially, [the] many of whom evidence indicates lack access to language-based AAC. Having ready access to language-based communication and literacy tools are essential to safeguarding and securing all of our human and civil rights. In our written communications and meetings with officials with the White House Domestic Policy Council, OSERS, NIDILRR, NIH, NIDCD and others, we have conveyed that actions must be taken to remedy both evils.

For these reasons, CommunicationFIRST recommends that the federal government and others prioritize and fund longitudinal participatory action R&D efforts co-led by people who need AAC to advance the following:

#1. Sustained research, demonstration, and system change efforts should be carried out at the federal and state levels to identify ways to remedy the reasons why people with congenital and acquired disabilities who need AAC and literacy support are denied them, as well as the impacts this has on rights to community integration, effective communication, and civil liberties.

Such research should examine the extent to which the use of standardized IQ assessments and similar instruments produce valid non-discriminatory results when used to assess people who have fine motor disabilities and need but lack language-based AAC. CommunicationFIRST has developed an extensive bibliography of studies that question the valid use of such instruments for this purpose. A meta analysis of all relevant studies is vital.

Research, including ethnographic and similar studies, is desperately needed to learn why so many people are illiterate, as well as why and how a relative few of us escaped this fate. Disability alone cannot be used to explain it, and literacy is essential to freedom. The costs and consequences of being illiterate are gruesome for any and are spiraling in the digital age. This is especially true for those who must spell out what we say.

#2. The nation should invest in, implement, and refine strategies that demonstratively enhance literacy opportunities and outcomes for the estimated 5 million of its people who cannot rely on spoken or signed language to live our lives. People who need AAC should be afforded access to communication and literacy support at every stage of life, from the youngest young to the oldest old.

#3. Black, Indigenous, Brown, and non-English-using children and adults who need AAC face enormous barriers obtaining it and egregious discrimination because of it. The federal government should prioritize participatory action R&D efforts that identify and remedy it.

#4. The Census Bureau and other federal agencies should collect and use population based and administrative data to bolster the everyday participation of all who need AAC. No federal population survey gathers any data on us. Disturbing inferences can be made based on data from agencies like OSERS and the Centers on Medicare and Medicaid Services on the egregious discrimination and harm that many we represent endure. But until we are officially counted, we will not count. Instead, many will continue to be denied effective AAC, denied an education, wrongly labeled and defamed, kept illiterate, segregated, institutionalized for life, subjected to extreme isolation, violence, social death, receive substandard health care, and die when doctors prescribe our lives and deem us unworthy. Going uncounted makes all this inevitable. It means we are not seen, we are not heard, and we do not matter. Lives of enforced silence and illiteracy exact the same toll.

#5. A report on the status of children and adults who require AAC should be issued in 2025 to mark the 50th anniversary of P.L. 94-142, the precursor to IDEA, and the 35th anniversary of the Americans with Disabilities Act, and the 60th anniversary of the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

When I was growing up, a public service ad was shown on our television several times a day. It declared reading is fundamental. I believed it then and even more today.

I hope what I have shared will spark thought, conversations, and participatory action research to improve the lives and futures of all people needing AAC. Thank you for your commitment and leadership.

Download in PDF form here.