by endever* corbin

This guest blog is adapted from a presentation given at the August 2021 Reinventing Quality conference.

I’m endever*, I go by they/them pronouns, and I’m a mostly nonspeaking autistic self-advocate. I focus a lot of my writing and presentations on my experiences with AAC—augmentative and alternative communication.

Equitable access to healthcare for people who can’t fully rely on speech to communicate is really important to me as an AAC user who is in frequent contact with the medical system. I have a few physical conditions easily maintained by medication, but my chronic mental illnesses are more severe and harder to manage.

Equitable access to healthcare for people who can’t fully rely on speech to communicate is really important to me as an AAC user who is in frequent contact with the medical system. I have a few physical conditions easily maintained by medication, but my chronic mental illnesses are more severe and harder to manage.

I see outpatient providers at minimum once a week, and off and on I need higher levels of care such as intensive outpatient programs or hospitalizations. I rarely use mouthwords these days, and because of that these healthcare systems often make it really difficult for me to utilize services. Today I’m going to present examples of barriers AAC users like me might face in healthcare.

I want to start by telling you about the biggest breach of communication autonomy I experience. On more than one occasion, hospitals have taken away my communication device. (They say the presence of any electronic device with a camera function violates confidentiality.) This has happened to me multiple times. Every time has been traumatic.

Not having a way to produce an audible “NO” or “STOP” makes someone incredibly vulnerable; in a medical setting, it is terrifying. When you’re under care for mental health issues, you are always at risk of being held against your will, restrained, and secluded. And the only protection you have is convincing someone you are healthy enough to make your own decisions.

So what if you can’t say much—or anything—at all?

If the people in charge of monitoring my mental state see me stimming, hitting my head, and not making eye contact, but don’t allow me to explain what’s going on inside, how are they going to figure out my mental state? What will they decide about whether I can leave the premises, “need” to be restrained or secluded, can consent to treatment or testing, can contact my friends, and about my other rights?

I am lucky that I am comfortable using different modes of communication. When one of my communication methods is restricted either by my external circumstances or my disabilities, I am able to switch to a different method and still get my point across. I use my device, American Sign Language (ASL), letterboards, and sometimes mouthwords, often changing back and forth within a single conversation or even sentence. Unfortunately, the fact that I switch between these can make fully-speaking people think I’m able to communicate 100% of the time with 100% reliability with any single one of these communication methods. Believe me, if that were the case, that’s exactly what I’d do! I know it would make them treat me better. But, no, I switch between communication methods because my abilities and impairments and environments fluctuate.

What this means for hospitals is that I come in with my device and letterboard and they think taking away the device will have a negligible impact. Or they find out I use sign language interpreters for some medical appointments and assume that’s sufficient access to communication. Folks, there is no substitute for access to any given communication method. You can’t decide for a disabled person which forms of communication are going to work for them, and when. Only the individual communicator can decide that.

Sure, I may decide in the moment that I am able to substitute one method for another. Maybe I feel able to both sign and select pictures to express a certain sentiment, and so I just pick one, and that’s great. But the access itself? The chance to choose? You can’t take that away and assume that anything else suffices in its place.

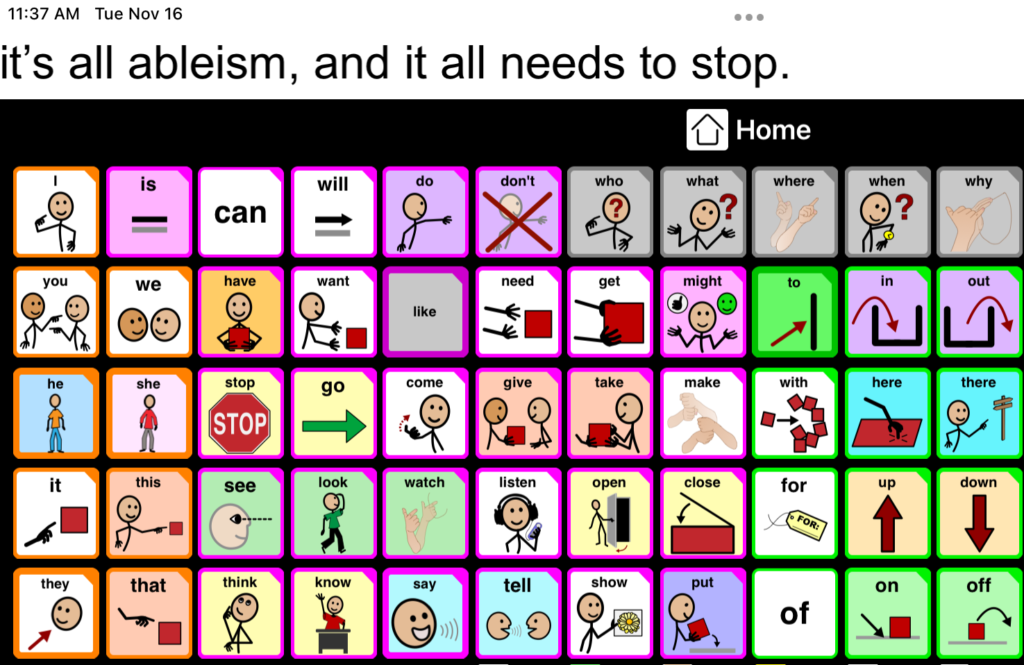

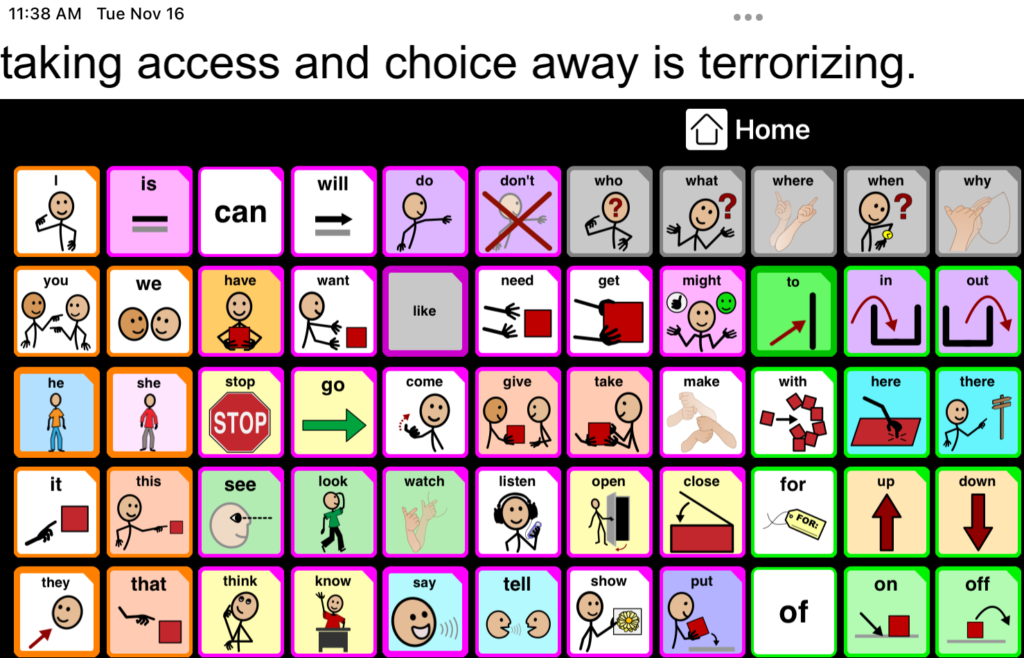

Taking access and choice away is terrorizing. There will always be things I need to say a certain way, and times I can only say things one way. If I don’t have autonomy over that choice, whatever authority took it away now has almost infinite power over me. And that’s me, someone who is often able to use more than one kind of AAC. I can only imagine the feeling of helplessness for someone whose only communication method is restricted—whether that’s a high tech device, or another person who supports their letterboarding—the dread, and trauma, of knowing that there is just zero chance of communicating.

Taking access and choice away is terrorizing. There will always be things I need to say a certain way, and times I can only say things one way. If I don’t have autonomy over that choice, whatever authority took it away now has almost infinite power over me. And that’s me, someone who is often able to use more than one kind of AAC. I can only imagine the feeling of helplessness for someone whose only communication method is restricted—whether that’s a high tech device, or another person who supports their letterboarding—the dread, and trauma, of knowing that there is just zero chance of communicating.

Sometimes hospitals think it’s an okay compromise to limit my access to my communication device (or to interpreters) only to the times I am with hospital staff. This isn’t equal access. They’re not taping everyone else’s mouths shut between meetings with medical providers. I want and should be able to ask the night shift for a snack, thank the person cleaning my room, talk to my roommate, socialize with other patients, and communicate in general whenever I have needs. My communication shouldn’t be limited to whenever a doctor or nurse is ready to come talk to me on their own schedule.

During COVID, with no visitors allowed on the unit, not being allowed a device or phone was especially harsh. Other patients on the unit weren’t good at reading my letterboarding (I go kind of fast), so I felt isolated and lonely. Meanwhile, I couldn’t text my friends, and the hospital’s camera-free tablets were rarely available for me to send Twitter messages to people on the outside. At one point I asked for a TTY so I could at least call my friend. It wasn’t working. Obviously, a nonfunctioning device is not access. Ironically, this specific hospital did have a good policy allowing exceptions to the no-visitors rule for patients who needed support people for communication. But no matter who in the administration sympathetic nurses took my situation to, I continued to be denied full-time access to my device.

Only after filing a second grievance with this hospital did they say they would purchase a device with my AAC app on it that I would be allowed to use for the duration of any future stays. They said this solution would also allow me to access Twitter and email to connect with online friends at my leisure. I explained to them that I will need to be able to download my highly customized AAC app’s user profile at the start of my visit and have my data fully deleted upon discharge. They agreed, yet success would depend on my capacity at the time whether I’d be able to do this independently or not (they don’t have any clue how to operate the app). I asked them to add several other commonly used AAC apps, in case they had other patients come in who needed access. But of course, if they don’t know how to operate those either, they may not be able to support someone else in uploading their customized settings, if that is even a possibility on every app.

While this arrangement wouldn’t necessarily put the hospital in compliance with equal access laws, it would probably make any future visits much better for me. Unfortunately, since I gave the original version of this presentation, I did have to return to this hospital. No one working there knew what I was talking about, or could find any information on it, when I explained the promised arrangement. And the patient services representative I had done all the negotiating with was out on parental leave.

I only had my letterboard for four nights in the emergency department (or some of that time, virtually nothing, as some nurses couldn’t read it). Once on a unit the staff there arranged for me to have a 1:1 staff during all my waking hours, so that they could supervise my tablet use and make sure I wasn’t using the camera. I was grateful at that point to have any access, but having a 1:1 isn’t a least restrictive setting by any means.

Limiting access to an AAC user’s full range of preferred communication methods is a primary concern when it comes to equitable patient experiences. While for me the common scenario is having my device confiscated, for other people it can be limited visitor policies preventing them from accessing communication supports, or nurses placing communication supports out of reach, or no access to interpreters.

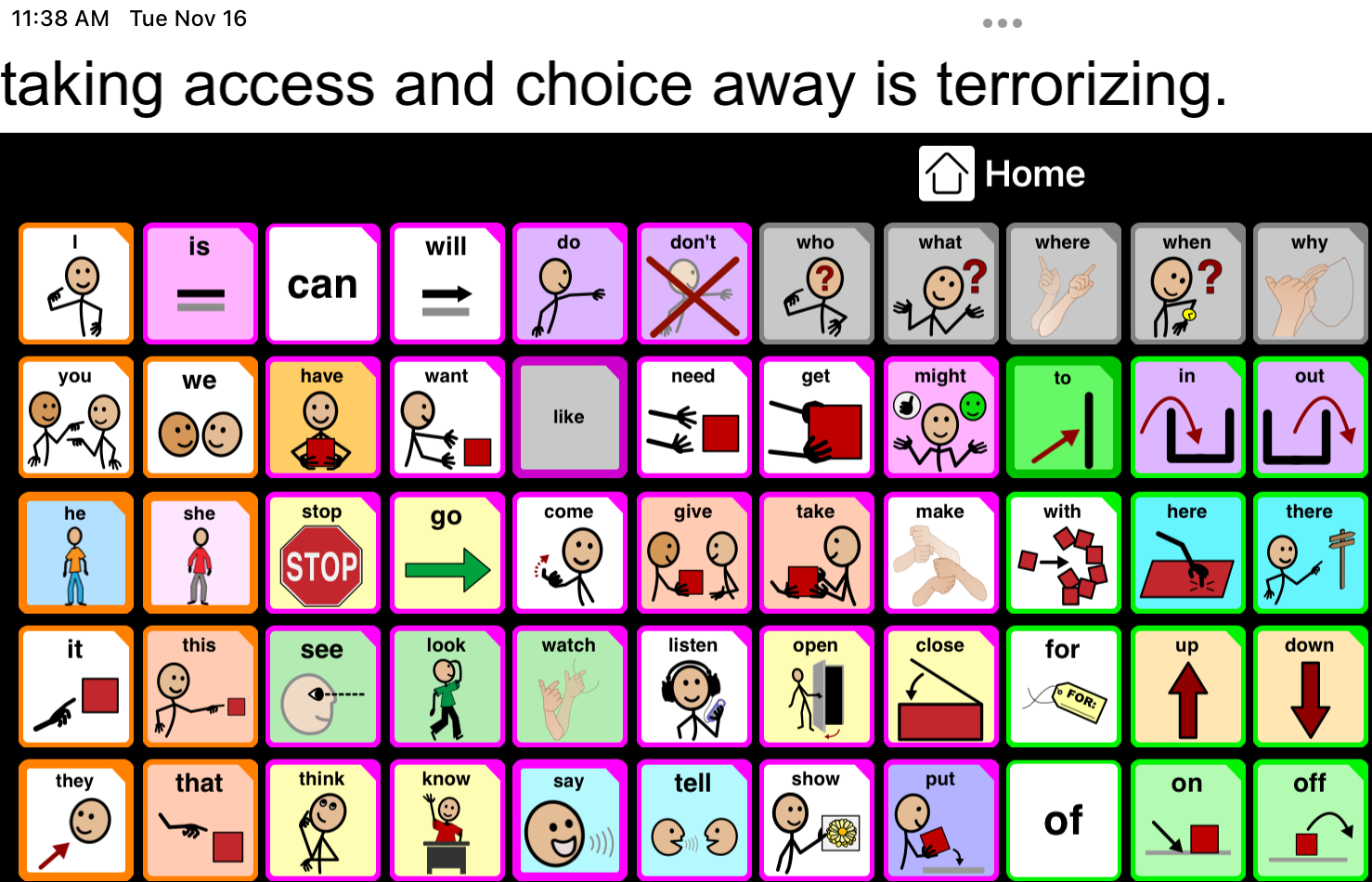

It’s all ableism, and it all needs to stop. People who can’t rely on mouthwords deserve to express ourselves, report symptoms, ask questions, refuse treatments and tests, and give informed consent just as much as fully speaking people do.

But it’s not just hospitals taking away AAC that interferes with our experiences accessing healthcare. There’s also the matter of literal access—not what happens once we’re there, but whether we are able to even get an appointment. And honestly what this comes down to for a lot of us, besides insurance and financial issues, is abled culture’s overemphasis on phone calls. For many of you, picking up the phone may be the quickest way to set an appointment or talk to your medical provider, but for many AAC users it is an insurmountable barrier standing between us and healthcare.

I can use text relay on my laptop to make outgoing calls, or if I know to expect a phone appointment I can make a point to be by my computer at the right time. (In text relay calls, I type my words for an operator to speak to the caller, and then the operator types the caller’s words in response for me to read.) But even then, the delay inherent in relay-based conversations means it might take fifteen minutes just to schedule an appointment, and when talking with a provider I may not be able to cover my concerns in the standard allotment of time. Some AAC users put their phone on speaker next to their device, but too often people hang up on us when we try that, thinking our voices are robot spam calls. Some of us have support people place calls for us while we spell things out beside them. But that can give rise to HIPAA issues when doctors or insurance companies won’t even let us give them information about our medical care if we can’t orally consent to our support person being present. It’s just a mess, is what I’m saying.

![]() I want to also touch on the way stigma against people with communication disabilities creates a hostile environment that may get in the way of our equitable access to healthcare. One example of this is when providers talk to my support worker or interpreters about me instead of talking directly to me. Not only does this inevitably lead to them misgendering me, it’s acting as if I can’t understand what’s going on, or don’t have anything to contribute. They’re treating me like I’m not even a real person. This is common: healthcare providers consistently doubt the competence of people who don’t use mouthwords. They may question whether we can understand language at all, accurately report pain or symptoms, and make our own decisions.

I want to also touch on the way stigma against people with communication disabilities creates a hostile environment that may get in the way of our equitable access to healthcare. One example of this is when providers talk to my support worker or interpreters about me instead of talking directly to me. Not only does this inevitably lead to them misgendering me, it’s acting as if I can’t understand what’s going on, or don’t have anything to contribute. They’re treating me like I’m not even a real person. This is common: healthcare providers consistently doubt the competence of people who don’t use mouthwords. They may question whether we can understand language at all, accurately report pain or symptoms, and make our own decisions.

When filling out informed consent forms I have been asked whether I can sign legal documents for myself—apparently not based on anything but the fact that I was using symbols-based AAC. This scenario is so familiar that many trans part-time AAC users decide to force ourselves to speak, no matter the cost, for all care related to gender transition—for fear that if we use AAC we will be deemed incompetent to know our own genders and consent to transition.

These examples are only the tip of the iceberg when it comes to fully speaking people doubting nonspeaking and semispeaking people’s ability to learn, communicate, understand, and make decisions. There’s a reason the first maxim you hear in the AAC field is “presume competence.” People don’t.

There are things providers have done right, and things outside of the healthcare setting that I think of as protective factors supporting my access to healthcare, and that’s important for you to know too.

My case manager at my clinic has been great about trying to call ahead to other providers and hospitals to advocate for my access to my device and to fill them in on what’s been going on so I don’t have to type everything out all over again when I get there. I remember one nurse in the psychiatric ER (who knew from my repeated begging that I was frustrated with only having a letterboard 24/7) noticed me perk up while signing with a Deaf patient. When they saw that, they offered to arrange an interpreter for me to interact with doctors if I wanted one. I think that was the first time I used an interpreter in a medical setting, and it gave me the confidence to request one in the future.

I also have had a good experience lately with a new provider who pauses our conversations frequently to ask if I have any questions, rather than barreling on like most doctors do, leaving me no time to process and express myself.

Many of the protective factors I believe have positively impacted my access to healthcare revolve around being part of a strong self-advocacy community that includes others who can’t rely on speech to be understood.

First of all, being introduced to AAC by folks who are multimodal communicators is a huge reason I am comfortable switching between methods, so that has set me up well for coping as best I can when medical environments restrict my AAC options.

Secondly, the opportunity to connect with other AAC users around what vocabulary I should add to my symbols-based app to be able to have full conversations with my medical providers has been invaluable. It’s one thing to have the default vocabulary, or to add things based on a generic list. But talking to others with similar health concerns about what other words I should add—and what symbols to use for them—has made a big difference.

Along those lines, I have been inspired by others’ medical boards full of phrases like “don’t touch me,” “what are my next steps,” and “I need more information.” I haven’t yet made my own folder for medical self-advocacy, but being around folks who are confident in standing up for themselves and communicating in whatever way works best for them has really empowered me to fight for my right to access healthcare in a safe, accessible, and affirming environment.

My recommendation for other disabled people trying to access healthcare: surround yourself with strong self-advocates! There is a kind of power you can pick up almost by osmosis from being around people like us who are outspoken and supportive of all the different ways we move and talk in this world. Take this to heart if you are a caregiver or provider too. Make sure the disabled folks you support have every opportunity to be in community with disabled advocates who can role model what it looks like to assert their right to equal access.

And for folks with communication disabilities, remember that self-advocacy often starts with refusal. That doesn’t mean you have to be able to speak a nice, polite, “no thank you” with your mouth. It means you get to say “no” however works best for you. It means pushing away when a doctor tries to do something you don’t want. It means ignoring a speech therapist who is trying to get you to use mouth words. It means not shutting up when you are treated badly. And it means wrapping your arms around your communication device and holding on for dear life when a nurse tries to take it away.

Whatever it is you want to say is important, no matter how you say it.

endever* corbin is a mostly nonspeaking autistic self-advocate who loves augmentative and alternative communication (AAC)! They enjoy helping moderate the weekly Twitter conversation called #AutChat, blogging about disability, and giving presentations about autism and AAC. They are also trans, queer, mentally ill, low income, and not ashamed of any of it. They have lots of opinions about healthcare accessibility, communication rights, disability justice, and Harry Potter.