This resource includes quick tips written by AAC users on organizing and hosting online meetings with AAC users. The complete guide can be accessed here.

These Quick Tips include some of the most important things to keep in mind when planning for meaningful inclusion and participation of our community in digital or online meetings. The complete version of this guide contains detailed suggestions for improving online meeting access for augmentative and alternative communication (AAC) users and others who may need speech-related meeting accommodations.

Give us the time we need. Listen.

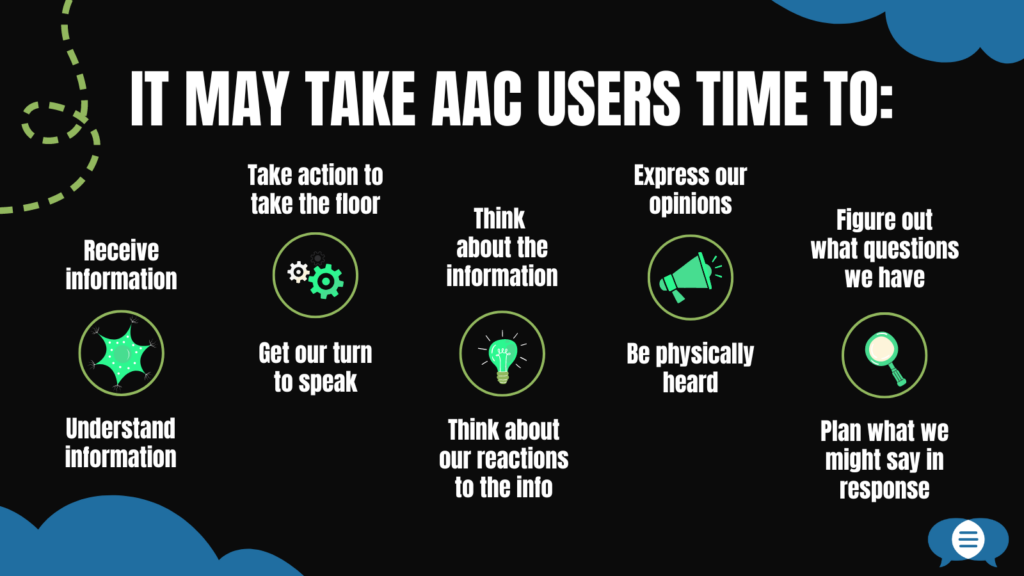

Most AAC users communicate more slowly than people who can use speech fluently to be understood. The average non-speech-disabled speaker of English speaks 125-150 words per minute; it is not uncommon for someone who uses AAC to communicate 5-10 words per minute.

- Consider an asynchronous or a hybrid option. The pace of most synchronous (real-time) meetings favors people who can speak fluently. That disadvantages us.¹ Asynchronous meetings (e.g., by email or instant messaging) allow us to take as much time as we need to respond, and don’t require us to be ready to communicate at a specific time, among other benefits. If asynchronous communication can achieve the purpose of the meeting, consider offering it as an option or as an alternative.

- Be respectful while we are preparing our message. If you see or hear that an AAC user is typing, spelling, programming, or otherwise composing their message, wait for them to finish before you say anything more. Give us the full opportunity to take our turn, ensure that the conversation doesn’t move on without us, and allow us to concentrate. And above all, be patient. Embrace the silence. It’s only awkward if you make it so.

- Avoid surprises whenever possible, and give us time to prepare. Schedule at least two weeks in advance whenever possible. Plan and share what you can in advance, including agendas, slides, or even “run of show” documents. Make sure everyone understands how to get in to the meeting. Share contact information (text or email format) so if someone hits a snag, help is available.

Keep in mind that many of us have motor disabilities.

Keep in mind that many of us have motor disabilities.

The clicks, taps, swipes, and keyboard presses involved in virtual meetings may present barriers to anyone with a motor disability, but there are ways to lessen the load.

- Require as few motor movements as possible to participate in the meeting. For example, even if you have sent out a calendar marker with the meeting link, send out a reminder email with the link at the top of your email, not the end, to eliminate the need to scroll or double click on a Zoom invitation. Never require participants to manually enter a passcode to get into the meeting. There are other ways to ensure security.

- Ignore accidental motor movements. For example, we may send a message before we are done, but if we’re still typing, we’re still talking.

- Anticipate that attendees will use different ways to communicate in the meeting. Gestures and expressions such as nodding or shaking heads, raising hands, giving a thumbs up, or smiling may be impossible for some of us. Clicking the “raise hand” button to speak, clicking on a link in the chat, or adjusting a camera may also be out of the question.

Keep in mind that many of us have cognitive disabilities.

We may need extra time to process or consider new information, decide what we think, and articulate those thoughts. It may be difficult for us to process a lot of information or multiple topics at once. Giving us time and space to process gives us a better chance to participate equally.

- Share meeting materials as early as possible. Send the agenda, questions, or slides a few days or weeks in advance. For most of us, a day or two won’t be enough time. At best, we’ll be unprepared or unable to meaningfully participate; at worst, we’ll be actively distressed and dysregulated by the lack of information, pace, and expectations set even before the meeting starts.

- Offer pre-meeting and post-meeting multi-format sessions for anyone who might benefit. Pre- and post-meeting exchanges provide more time to process and ask questions about the meeting topics and agenda, and will help us get familiar with the platform. For example, Zoom has an asynchronous chat where participants can chat prior to a meeting, during a meeting, and after a meeting where the whole conversation is visible the whole time.

Understand speech privilege, and be proactive in leveling the communication playing field.

It takes time and effort for most people who use AAC to communicate with language. Even when we are accommodated for that time and effort, there may be barriers we cannot surmount on our own.

- If you have easy access to speech, use it to make space for us. Notice when we are being spoken over, and use your privilege to help make timely space for us. You can politely pause the group conversation to make space for your fellow attendees with phrases like: “Hang on, I think Bob is typing,” “Were you going to say something, Jordyn?” and “Let’s wait until Lateef is done, please.” This can help model respectful behavior and can go a long way. Take the time to enforce any established meeting rules or norms to ensure our equitable collaboration, like reading the chat box in real time, before the next speaker begins to speak. If it seems our ideas are not getting as much attention, time, or space as ideas from other participants, take the time to highlight them. Use your speech privilege to privilege us.

- Appoint a communication access monitor. An access monitor reads the chat aloud as soon as possible without interrupting someone to ensure that people who cannot read the chat themselves have access to what’s being said; to ensure that people who are using the chat to communicate are heard and understood, not ignored; and to help ensure that points are being made before the discussion moves on to a different topic. A communication access monitor should also pay attention to who is participating and who is not, and make sure that everyone has the time and access they need to participate. They might also provide descriptions of anything that is happening visually during the meeting (such as someone who is nodding their head in agreement, laughing, or giving a thumbs up), ask people to pause discussion while someone is typing, and turn cameras and microphones off and on as needed. It’s best to appoint just one person who has no other role that may distract them.

- Never expect people to fully address an issue on the spot. Many of us need time to process and think, to decide on our opinion, to compose our responses, and to type or otherwise communicate our responses in a way others can understand. Prepare well. Whenever possible, share questions and discussion topics before a meeting, and always allow for the possibility of receiving (and engaging with) ideas and thoughts after the meeting in a variety of ways. Any vote or important decision should not be rushed, and may be better concluded by asynchronous discussion and voting or by consensus.

Don’t let accessibility be an afterthought.

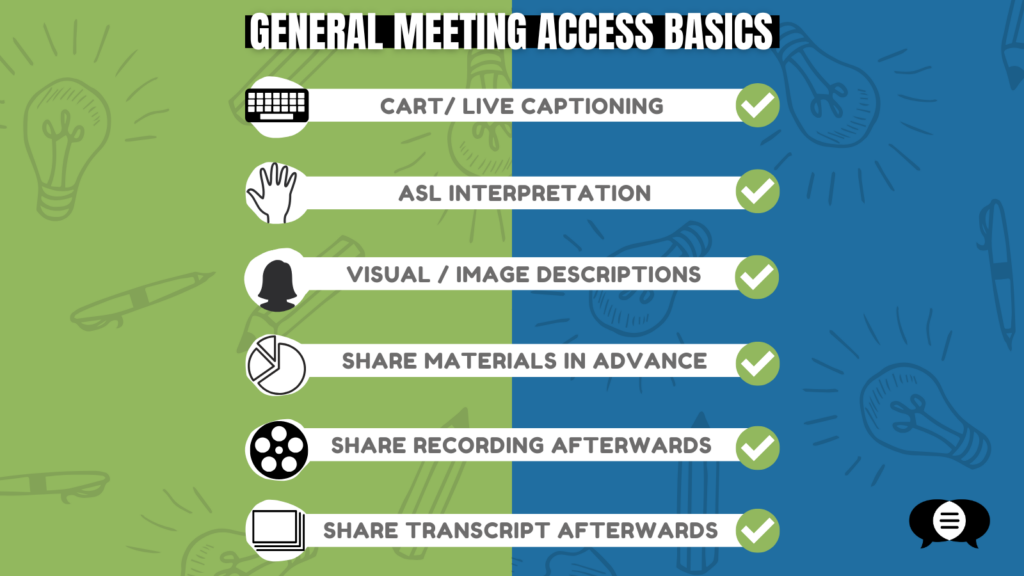

It’s standard practice to ask attendees about their accessibility needs, but the onus shouldn’t have to be on us. Meetings can be designed in a way that by default includes and allows for multiple means of access, communication, and participation, so that accommodations may not need to be requested at all.

- Don’t assume that what’s worked before will work at the next meeting. Work collaboratively with participants to consider our access expertise and what platform is most accessible for us and others. Be flexible, and respect the strategies participants have already developed. Plan for the possibility of conflicting access needs.

- Think about everyone who’s attending, especially when planning a public webinar. Plan (and budget) for external access providers, like sign language interpreters, spoken language interpreters, and CART providers to ensure accurate captions. Think about how to share documents and how to best share screen real estate. Talk through your ground rules and make sure everyone is on the same page with them.

- Ask, ask, ask. As with all things accessibility and all things human, there is no substitute for direct communication. No tips or guidelines will be appropriate for every single person with a speech disability. One strategy may be indispensable for one person while being an obstacle to another. Use this guide to generate ideas, not to dictate decisions. At the same time, communication goes both ways. AAC users are only human, and they may not have all the answers. Treat us as equal partners with you in this process.

For additional and more detailed tips, the full guide can be accessed here.

Download Quick Tips for Online Meetings with AAC Users, by AAC Users in PDF form here.

¹ We write these tips as AAC users ourselves, but we do not claim to represent all AAC users and all kinds of AAC. Because of this, we alternate between the use of second person (using words like “us,” “we,” and “our”) and third person (using words like “AAC users” and “participants”).