By Sophie Bohnen

LIVING FULLY

When I first lost my voice, I didn’t think much of it. I had just gotten over the flu and a bout of laryngitis. I assumed I’d wake up the next day, speaking clearly again, as if nothing had happened. But days turned into weeks, and weeks turned into months, and my voice did not return. One doctor’s appointment followed the next until I was eventually diagnosed with Laryngeal Dystonia, a rare condition that affects the muscles controlling my voice. While there are treatment options, some types of the condition—like mine—are more difficult, if not impossible, to treat. Eventually, I had to confront reality: my voice wasn’t coming back, at least not in the way I had hoped. If I wanted to live fully, I couldn’t wait any longer. I had to begin again.

NAVIGATING MY NEW NORMAL

Adjusting to life with a voice condition has been a journey dotted with grief, anger, and shame. Mundane interactions turned into mountains to climb, and run-ins with friends, acquaintances, and neighbors filled me with dread. Everyday interactions—things I took for granted not long ago—became impossible, or significant challenges. Ordering coffee, for example, is no longer just a quick transaction. If I want my order to be heard, I have to lean in close. “Hi, I have no voice,” I whisper, and often, they lean in, too. It’s an oddly intimate moment, brushing cheeks with a stranger, whispering in their ear just to get a cup of coffee. As I leave, they often say, “I hope you get your voice back soon!”

At first, I didn’t know how to respond. Today, a simple “Thanks, me too” feels right. Because although unlikely, it’s true—I do hope my voice comes back.

FINDING MY VOICE IN ADVOCACY

I haven’t fully embraced my new voice, but I’ve stopped waiting for my old one to return. Since then, my experience of the world has changed drastically. There are many spaces where my ability to participate depends entirely on whether others make room for me. This power imbalance is one I have yet to come to terms with.

It’s infinitely harder to succeed in our world for people with disabilities—not necessarily because of the disability itself, but because of societal ideals, ableism, and systemic barriers that reinforce exclusion. I quickly had to learn to stand up for myself. Oftentimes, I’m the only one who will.

For the better part of a year, an acquaintance commented on the quality of my voice every time we interacted: “Oh, your voice is getting better!” When I denied his observation, he was insistent. “Yes, it is!” he’d say, as though he were the expert on my condition. His remarks were rooted in ableism and the idea of linear progress. His statements were also simply untrue, and a constant reminder of what I was living with. Eventually, because of all that built-up frustration, I snapped and told him off.

That moment wasn’t my most graceful, but it marked a turning point in how I advocate for myself. I’ve learned that setting boundaries is an important part of living a dignified life, and clear communication, even if it’s without words, creates space for mutual understanding.

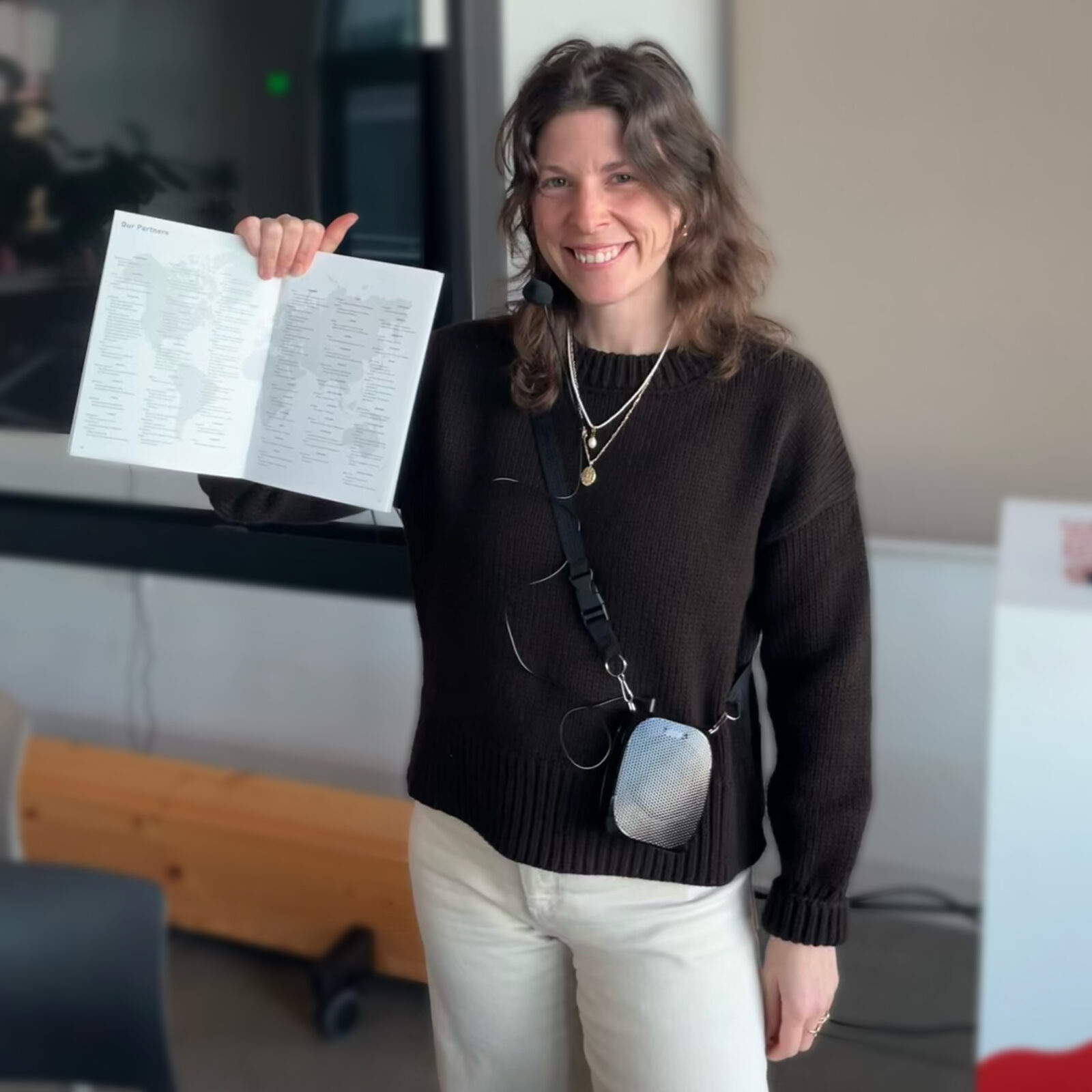

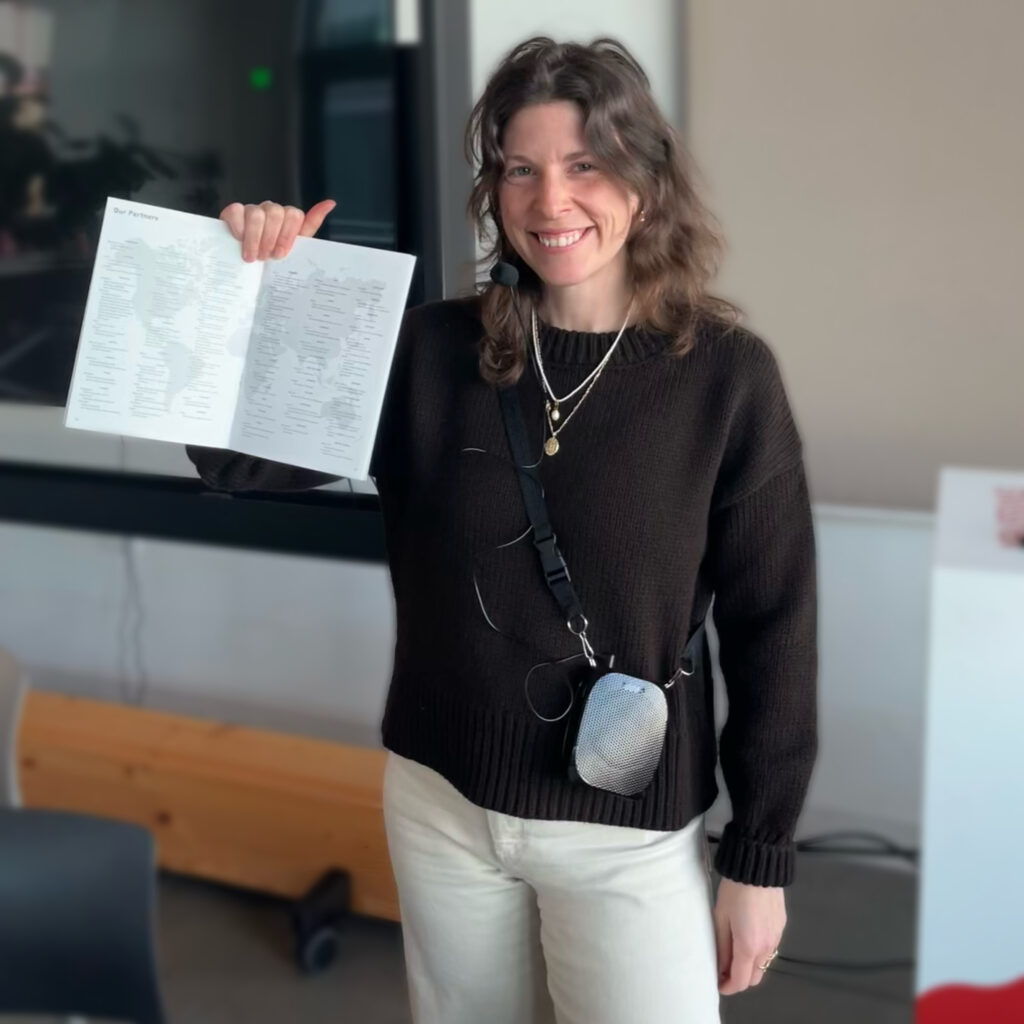

Now, I introduce myself with confidence and a voice amplification device: “Hi, my name is Sophie. I have a voice condition called Laryngeal Dystonia, and this is just how I sound.” I make sure it doesn’t sound like an apology. I’m acutely aware that I’m not just speaking for myself in those moments; I’m advocating for the broader voice- and speech disability community. Having an unconventional voice is nothing to be ashamed of.

There are so many people like me who struggle to speak or be understood due to conditions like ALS, Cerebral Palsy, Vocal Cord Paralysis, Autism, Parkinson’s Disease, and Stuttering. And while the world doesn’t always make space for us, I’ve resolved to claim it anyway—for myself, the millions around the globe that face difficulty being understood using their own voices, and everyone else that is navigating a world that wasn’t built with them in mind.

Sophie Bohnen is a San Francisco-based marketing and communications professional who has a passion for turning big ideas into reality. Sophie is a trained journalist with a decade of experience in a variety of writing professions. She is the author of The Listening Newsletter and co-host of the CreativeMornings San Francisco chapter where she organizes free monthly events for the local creative community. Sophie lives with Laryngeal Dystonia, a condition that affects the muscles controlling her voice, and has been navigating the world with a whisper since 2023. “When I first lost my voice,” Sophie says, “I felt completely lost and alone. I was desperate to hear stories from others like me. There are many untold stories of hardship and hope waiting to be shared.”

Call for Submissions: Tell your story! Ms. Bohnen is collecting essays about navigating life with a speech or voice disability or condition to be published in a collection to be called Still Speaking: A Collection of Essays on Navigating Life with Atypical Speech. Ms. Bohnen is looking to include the stories of people living with ALS, Autism, Aphasia, Cerebral Palsy, Spasmodic Dysphonia, Laryngeal Cancer, Vocal Cord Paralysis, Down Syndrome, Unexplained Voice Pain, Selective Mutism, Parkinson’s Disease, Stutter, or other conditions that make being understood with speech difficult. If you’re interested in contributing a 2,000- to 3,000-word essay about resilience, adaptation, or self-acceptance as a person with a speech-related disability, please submit your application to Ms. Bohnen by February 28, 2025, at this form. Before filling out the form, you don’t need to have a completed essay, just your story idea for the book. Ideally, the book will be available both in a digital format for e-readers and a printed version. Ms. Bohnen is currently looking for a publisher. Should she not find an interested publisher, she will look into self-publishing. Ms. Bohnen will also look into different ways of funding the project (crowdfunding, applying for grants, etc.) and is aiming to break even. If this will not be possible, she is prepared and willing to pay out of pocket to make this project happen as she truly believes it needs to exist in the world. If she is able to raise enough money, she will compensate the authors.

Download in PDF form here.